Infrastructure outages happen. Be one step ahead.

What is the "Disaster Tolerance" approach and why it's important to adopt it before the next crash arrives. Here's our take on the last AWS outage.

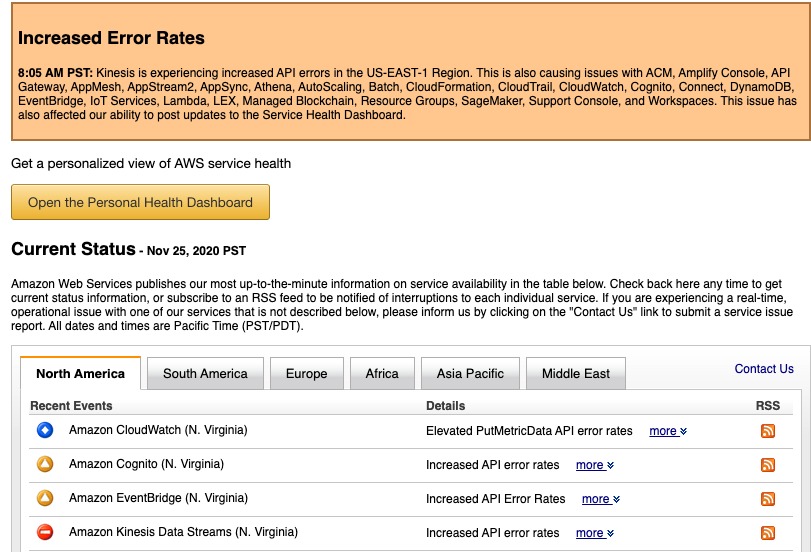

Sometime last Wednesday we started getting weird errors from our systems. Everything was up, the logs weren’t reporting any abnormal behavior, but some things just… failed (or didn’t happen at all). After a few more incidents we went to check the AWS Status page and realized that AWS had an outage (apparently this time they also reported the outage with delay, because the status report system was also affected).

Luckily for us, a simple region switch has returned everything to normal - but for a lot of companies, this wasn’t the case.

I strongly believe in the value of serverless. Having everything from computing to queues to DB’s and encryption without any need for maintenance, IT personnel, SRE crews, technicians, and other personnel required to maintain an on-prem framework is an enormous advantage. It allows companies to focus on what they do best and creates better infrastructure service for all of us.

But, serverless does not mean “Always Up”, and it definitely doesn’t make you automatically resilient.

Serverless is not “Always Up”

Each of the biggest cloud providers has had its own outages in the last few years: Azure, GCP and AWS, and in each of these outages, numerous customers were impacted. On average, since 2011, each of these cloud providers had a major outage at least once a year and numerous smaller outages impacting specific services.

We all need to accept that this problem is not going away. As Forrest Brazeal wrote, it might even get worse. The reason can be anything from a natural disaster or a terror attack to a system bug or even a well-intended system upgrade - But the fact that we pay a cloud provider to handle all these risks doesn’t make them all magically disappear, it just makes it someone else’s job to fix them.

Serverless does not equal resilliant

The fact that you moved your entire compute to Lambda, use SQS for queues, and rely on Aurora DB, does not make your application outage-resilient. If you don’t have your infrastructure available as an IaC and your data duplicated to another region, when an AWS region falls (and it will), you will be in the same pickle as the guy with numerous EC2 instances.

Shared responsibility model

When it comes to cloud security, AWS has a shared responsibility model. It basically says that they are responsible to protect the infrastructure, and you are responsible to protect the services you built with this infrastructure.

When it comes to availability, we think the same should apply too: the cloud provider is responsible to maintain the infrastructure, but you are responsible to maintain your services. In other words, it might be AWS’s job to fix the infrastructure, but it’s your job to handle the problem until they do.

How to prepare for an outage

Now that we have established the following:

- Outages are real, often, and here to stay.

- Serverless doesn’t make you automatically resilient to disasters.

The next question is how to prepare for these cases. Most people stop reading here, because they assume that disaster handling means you have to build a solution that will provide your customers with the same level of service they are used to, even when an outage occurs - which is usually a very difficult, expensive, and time-consuming task.

However, the most important thing to understand is that you don’t necessarily have to create full redundancy: You don’t necessarily have to provide your customers with the same level as service on an outage - but you do have to decide what you do want to provide them with when (not if) it happens.

Maybe it’s OK if your customers will be able to read-only for a couple of hours. Maybe it’s fine if your cheese-recognition filter won’t work on all their pictures, and maybe in your case, it’s fine if they won’t be able to update product prices - but you have to decide what is crucial to support, and what can wait.

IaC is your best friend

Disaster recovery with serverless is a huge issue, and each system has its own quirks to iron out when doing it (You can read more about AWS best practices for it here), but considering the basic 3 layers will get you a long way: your edge layer, data layer and compute layer.

Your edge layer is basically everything that connects your users to your services - mainly, your domains and CDN. Consider how your users will be able to reach your service in the case of a disaster and make sure that your DNS supports failover routing, so when stuff breaks, you will be able to easily divert traffic to your working site.

Your data layer is wherever you store your data - anything from standard RDB to your flavor of NoSQL to messaging queues: how can you make sure that you have a relevant copy of your data available even if the main site is down? Check out your cloud provider cross-regions synchronization solutions. Remember, your solution does not necessarily have to be fully concurrent - Maybe your DR use case can live well with data from 5 minutes ago?

Your compute layer is wherever you process your data. One of the benefits of going serverless is that this entire layer is usually easily replicable - if you use Infrastructure as Code solutions. When your infrastructure is part of your computation code, deploying it to another region can be a quick and easy solution to running your service in a beta location.

Sum Up

Serverless is the future. It removes a lot of unnecessary burden from your IT and DevOps teams and allows you to focus on your real business - but it’s not magic. It will gloriously crash every once in a while, and while it does lends itself to resiliency, you will need to make sure you take it into consideration when you design your solution in order to get it.

Comments powered by Disqus.